Do life’s worst experiences leave us permanently scarred? Or can they actually help us grow into stronger, more resilient people? It’s a tricky question, but there are certainly those who’ve been victims of terrible things, and nevertheless managed to thrive. There may be no better example than Edith Eva Eger. In 1944, Eger—who was 16 at the time—was rounded up with her Hungarian Jewish family and deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. There, she suffered unimaginable horrors, lost family members, and nearly died.

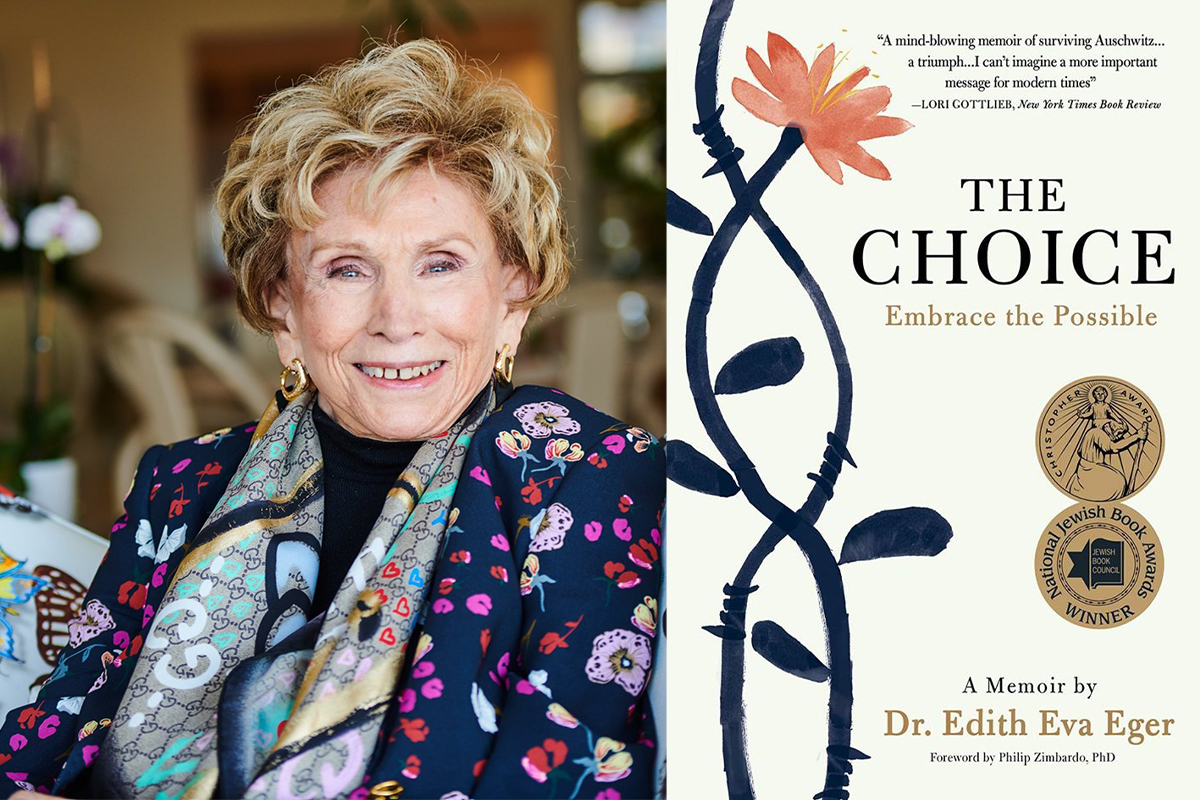

Decades later, after being rescued and emigrating to the U.S., Eger earned her Ph.D. in clinical psychology and began treating patients, using her own experiences to help them heal. In 2017, at the age of 90, Eger wrote her first book, The Choice: Embrace the Possible. Both a memoir of her harrowing story and an account of the many life lessons she learned practicing clinical psychology, Eger lays out a path for achieving happiness—no matter what life throws your way.

1. Suffering is universal, but victimhood is optional.

Victimization is not the same thing as victimhood. Victimization comes from the outside, and is pretty much unavoidable. At some point, we’ll all be made victims by other people, circumstances, or institutions over which we have no control. Victimhood, on the other hand, is internal and optional; it’s what happens when we choose to latch on to the experience of victimization.

Edith Eger learned this lesson as a teenager when she and her sister were imprisoned in Auschwitz, the notorious Nazi concentration camp. When their heads were shaved and clothes stripped, Edith’s older sister Magda turned to her and asked, “How do I look?” In that instant, Edith realized she had a choice—to pay attention to all she had lost, or to focus on what they still had. Choosing the latter, Edith complimented Magda’s eyes. “They’re so beautiful,” she said. “I never noticed them when they were covered up by all that hair.”

“To survive is to transcend your own needs,” Eger writes, “and commit yourself to someone or something outside yourself.”

“Victimhood, on the other hand, is internal and optional; it’s what happens when we choose to latch on to the experience of victimization.”

This same belief showed up in Eger’s dissertation research when she interviewed Holocaust survivors living in Israel. Many—but not all of them—were thriving. They’d gone back to school, started businesses, and built close friendships. The difference between the thrivers and the others seemed to be a simple belief: the belief that they could choose a different life in the present, and were not defined by the trauma of their past. “We can choose to be our own jailors, or we can choose to be free,” sums up the argument of Eger’s doctoral work.

2. True freedom is found internally.

As a concentration camp prisoner, Eger learned that even when she had no control over her external circumstances, she could choose how to respond internally. In one of the many mysterious selection lines she was forced to stand in at Auschwitz, the girl next to Eger said, “This line is death.” Eger responded, “We never know what the lines mean.” This ability to remain curious—to even cultivate a sense of wonder—became key to her physical and mental survival.

Later in life, as a practicing psychologist, Eger developed techniques for helping others discover their own inner strength. Working with an anorexic named Emma, Eger asked the young woman when she last remembered feeling happy and free, and Emma responded, “When I was five.” “Draw me a picture of that girl,” Eger instructed, and Emma drew a picture of a little girl dancing. The activity was helpful for Emma, and it woke something in Eger herself, who realized she regretted dropping her own youthful ambitions to dance. She took up ballet again, and though she never became a professional dancer, she began finishing her lectures with a ballet high kick—a tribute to her younger self, and a marker of choosing to acknowledge and accept the past rather than ruminating over what could have been.

3. Take responsibility for your feelings.

So often we blame others for our unhappiness in life. But by taking responsibility for our feelings—especially the negative ones—we also, subconsciously, take the first step toward freedom.

Eger learned this lesson for herself after her divorce, when she allowed herself to fully experience the feelings of jealousy, bitterness, and loneliness she’d been repressing. In so doing, she realized that feelings aren’t permanent; if we acknowledge and accept their presence, they move and change and can be released. After a night of crying and feeling sorry for herself for a divorce she chose, Eger realized she felt more at peace, an insight that became crucial in her therapeutic approach as well.

“When we take responsibility for our feelings, we take responsibility for our lives.”

One of her patients, a former Army captain named Jason, was struggling with repressed rage at his wife, whose affair he had just discovered. Eger worked with Jason to develop a mantra he could use to more fully experience and manage his emotions: notice, accept, check, stay. The first step, noticing, involves acknowledging and naming the feeling as it arises. Although there is a broad spectrum, most feelings can be derived from a few primary emotions: sad, mad, glad, and scared. After noticing and accepting his feelings as his own, Jason learned to check in with his body, to acknowledge how they moved through him. By sitting with the unpleasant bodily sensations rather than running from them, he learned they were only temporary. Finally, Jason was ready to learn how to respond to his feelings in a healthier way, rather than trying to control them (and those around him).

When we take responsibility for our feelings, we take responsibility for our lives. Truly experiencing the range of human emotions, rather than suppressing our feelings, allows us to let go of negative experiences. Feelings can move through us quickly, but if we repress them, we may feel stuck in our pain for weeks, months, or even years.

4. Freeing ourselves involves taking risks.

Decades after her release from Auschwitz, Eger made a return visit to the shuttered camp. It was a huge emotional risk for her, bringing up painful feelings of anger, fear, and intense guilt. Back when she was a 16-year-old at Auschwitz, Eger had been approached by an officer who pointed at her mother and asked, “Is she your mother or your sister?” Without thinking, Edith replied “mother,” a word that changed the course of her life—her mother was immediately sent to a line of women and children who would be gassed.

Eger had carried the trauma of this moment with her for years. Only by taking the risky move of returning to Auschwitz and facing the memory squarely was she able to finally forgive herself, and even forgive the Nazis who killed her mother.

Eger took this personal risk after working with her patient Jason, who was full of anger—toward his wife, toward his abusive father, and most importantly, toward himself. Eger helped Jason see that anger is only ever the outer edge of a much deeper feeling. For Jason—and for Eger—that inner feeling was fear. Jason was masking his fear of incompetence with an outward expression of anger, and Edith was masking her fear with anger directed inward, blaming herself for her mother’s death and unable to forgive herself.

“Taking risks can occur only after we’ve learned that we have the power to change our beliefs and feelings.”

When we take risks, we step out of the feedback loop that has us locked into repeating the same behaviors over and over again. Taking risks can occur only after we’ve learned that we have the power to change our beliefs and feelings. By accepting our fear instead of hiding from it, we can move forward in healing our relationships with others and with ourselves. And, as Eger writes, “You can’t feel love and fear at the same time.”

5. Forgiveness is the key to freedom.

When Eger first started working with a therapist herself, she realized she needed to accept and express her own anger—toward Hitler, toward her husband, and most importantly, toward herself. While her anger made her want to lash out, she knew that “revenge doesn’t make you free.” While forgiveness is rarely easy, it is absolutely necessary in the process of healing from trauma and suffering.

In her own journey toward healing, Edith learned first to forgive those around her, including her husband, who had prioritized his career over their marriage. Then, on a trip to Germany, she consciously chose to forgive Hitler, walking up the path to the Nazi leader’s Eagle’s Nest retreat and shouting out “I release you!” Of course, forgiving Hitler did not mean condoning his actions. Rather, it meant releasing the part of herself that had spent decades wrestling with the fear and anger he caused. Finally, in returning to Auschwitz, she learned to forgive herself.

Forgiving oneself is crucial, Eger writes, and goes a long way toward healing our relationships with those we love. In her therapeutic work, she treated one family whose dysfunctional dynamic could be traced back to the father’s guilt over carrying out an order during the Vietnam War that ended up getting his troops killed. Instead of acknowledging his guilt, he had directed his anger toward his family—exerting control in order not to show weakness. In working with Edith, he learned that exposing his fear and forgiving himself would make him a more approachable and loving father and husband, likely changing the family dynamics that were so ingrained.

When we first begin to heal, we may start by forgiving those around us. But unless we forgive ourselves, we can never truly achieve internal freedom.